Hello! I have returned from another inordinately long break in between posts to talk at length about things relating to dead people once again. I’ve been busy with Funeral School and my Funeral Job, and, through a fault that was entirely my own, had to spend the majority of my evenings that past couple of months catching up on notes and readings for my Funeral School courses so that I wouldn’t fail my exams this semester, WHOOPS. Then I wrote my exams and it was almost Christmas and we got really busy at work; then it was Christmas, and I was on call, and my husband broke his leg and it was just generally a bit of a disaster. BUT! Now there’s another long weekend, and I don’t have to work, and I still have two weeks before Funeral School starts up again, thus: time to blog!

I mentioned in my previous post that I was working on this post, and that they were somewhat related in that they both involve body-snatching, and the main character is a huge turd. That was not strictly true; what I actually meant was that I had had the idea for this post and found some sources, and then told myself I’d write it when I was less busy, without actually starting work on a draft or outline or anything that an organized person might do. Same thing, pretty much, right? Anyway, in Gordon Truesdale’s case, there was a little bit of satisfaction in knowing that karma took spectacular revenge on him for what was both a legitimate crime and a real dick move; however, that’s not going to be the case here, which is disappointing to say the least. The villain in this story happened to be wealthy, famous, and hugely respected in his field, and so, as is often the case in these circumstances, his behaviour, which was extremely unethical at best, and straight up criminal at worst, was just kind of glossed over and mostly forgotten about.

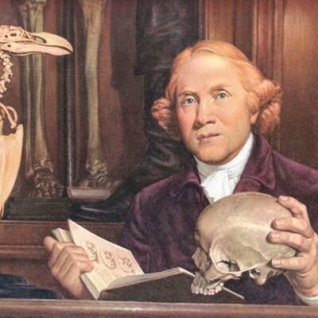

The villain of this story is John Hunter, the famed 18th century anatomist and surgeon. He was very clever and accomplished, and advanced medical science, I won’t argue that. However, I’m also not going to talk about any of his accomplishments here, because he’s already very famous (the man has a musuem named after him, after all), and because I want to focus on the victim of the story, Charles Byrne, whose body Hunter stole, desecrated, and put on display, where it remains to this day. In fact, what prompted me to research the details of this particular tale was the fact that, in the short biography of Hunter in my embalming textbook’s history section, it was addressed in a single, throwaway line after listing all of his achievements and contributions. “He did all of this great stuff; was a super genius and a pioneer in his field; the father of modern surgey; got a museum named after him, etc etc. Also one time he stole a guy’s dead body and put his bones on display.” Wait, what?

The name of the man whose body John Hunter stole was Charles Byrne. Byrne was a young Irishman who briefly earned a living in London during the 1780’s by exhibiting himself as O’Brien the Giant, inviting Londoners with nothing better to do to come a gawk at him for a small fee. At a time when the average male height was around 5’5″, Byrne was variously billed as being anywhere between 8′ and 8’4″, although his actual height as determined from his skeleton was probably closer to 7’7″ (which is nevertheless still very tall). Though he didn’t know it at the time, Byrne’s immense height (and his generally large body size) was the result of the condition knownas acromegaly, which is caused by tumors on the pituitary gland that affect the levels of growth hormone in the body, causing excessive growth. For any WWE fans reading, famously large wrestlers Andre the Giant and The Big Show also suffered from this condition, though Big Show was able to have surgery at some point to remove the tumor and return his growth hormone levels to normal.

Aside from making him extremely tall, Byrne’s condition likely also left him in no small amount of pain. Accounts of his early life refer to Byrne suffering from bouts of ‘growing pain’, probably as a result of frequent, rapid growth of his skeletal tissues. As well, he would probably have experienced chronic pain as he got older, and larger, due to the sheer mechanical stress on his body of existing as such a large human being. The physical pain of his existence, both acute and chronic, may also have been a significant factor in one of other notable facts of Byrne’s life as a London attraction: his heavy drinking. Byrne was known to make appearances while drunk, and cancelled numerous engagements due to inebriation. While it’s often reported that Byrne drank extremely heavily throughout the last few months of his life due to depression — the result of the unfortunate circumstance of having had his life savings (in the form of a bank note for £700) stolen from his pocket during a night on the town — in the longer term, his alcohol abuse was probably also a form of self medication against the pain of his condition.

In 1783, just over a year after arriving in London, Charles Byrne died at the age of 22. Though the last few months of his life were marked by pain, heavy drinking, and general ill-health (it is though that he was also suffering from tuberculosis at this time), Byrne was nevertheless keenly aware that Hunter knew who and where he was, and that the anatoomist had expressed a strong desire to ‘acquire’ Byrne’s body for his collection of anatomical oddities. In fact, Hunter went as far as to hire someone to follow Byrne around, renting a residence just a few doors down from where Byrne was living, so that he could be informed within moments when Byrne eventually died.

London newspapers, aware of both Byrne’s death, and the interest of Hunter and other anatomists in gaining access to his body, followed the story with breathless enthusiasm:

“Since the death of the Irish Giant, there have been more physical consultations held, than ever were convened to keep Harry the Eighth in existence. The object of these Aesculapian deliberations is to get the poor departed giant into their possession; for which purpose they wander after his remains from place to place, and mutter more fee, faw, fums than ever were breathed by the whole gigantic race, when they attempted to scale heaven and dethrone Jupiter.” (June 13, 1783)

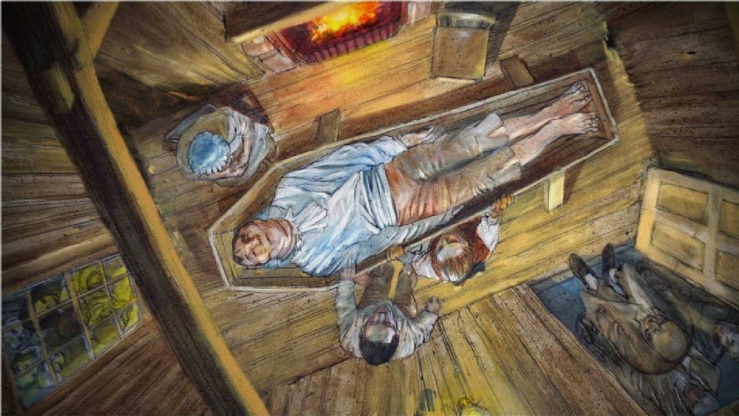

There was just one major flaw in the plan to gain control of Byrne’s corpse, one which, as we will see, Hunter was more than willing to ignore: Charles Byrne had no intention of allowing his body to be dissected. In fact, Byrne was so concerned about his body being used in this way, expressly against his wishes, that he directed his friends to seal his coffin and bury him at sea so that his body couldn’t be dug up by Ressurection men and sold to the anatomists. His friends, to their credit, tried to carry out Byrne’s wishes exactly as he requested, but Hunter had other ideas.

Byrne’s objection to having his body dissected was both moral and religious. In the 18th century, medical dissection was a controversial practice; something considered a necessary evil, at best. At the time, the only bodies that anatomists and surgeons were permitted to perform dissections on were those of executed criminals — having one’s body dissected was effectively a continuation of your punishment, and the threat was intended to act as an additional deterrent (as if the threat of execution wasn’t enough already). In addition, the Christian belief that one’s body must be whole in order for a person to be admitted to heaven and resurrected on Judgement Day, was much more strongly held on a societal level than it is today. So, not only did Byrne not want his body to be treated like those of the worst criminals, he was also deeply afraid that if that were to happen, he would not be able to go to heaven.

Hunter, as an anatomist, was well aware of this general objection to dissection, and it’s safe to assume that he was also aware of Byrne’s personal objection as well, since his request to be buried at sea, specifically to avoid this fate, was reported in the newspapers at the time of his death:

“In his last moments (it has been said) that he requested that his ponderous remains might be thrown into the sea, in order that his bones might be placed far out of the reach of the chirurgical fraternity.” (June 1, 1783)

Not to be deterred by something as consequential as a man’s dying wish, Hunter found out when and where Byrne’s friends were planning to carry out his burial-at-sea, and was able to bribe the undertaker who assisted them to switch out Byrne’s body and fill the coffin with stones while it was left unattended (fun fact: the bribe was reported to be £500, which would be roughly £71,000 today). While Byrne’s friends unknowingly transported a coffin full of rocks offshore and committed it to the ocean floor, Hunter spirited Byrne’s body back to London where, knowing that he had absolutely no claim to Byrne’s body and that what he had done was a crime, he hastily chopped it up and reduced it down to the skeleton. Although the authorities tended to turn a blind eye towards cases of body-snatching, the threat of retribution by loved ones of the deceased was real, and this, more than anything else, is likely what prompted Hunter to keep the bones hidden for 4 years before reassembling Byrne’s skeleton and putting it on display.

Aside from the complete disregard for Byrne’s humanity, the fact that, in the end, Hunter didn’t even examine Byrne’s body and learn something from it might be the most aggravating detail of this whole story, as we’re then left with nothing to redeem Hunter, and nothing that might have offered some minor comfort to Charles Byrne’s probably very dismayed spirit. The cause of Byrne’s gigantism (a pituitary tumor) wasn’t discovered until 1909, more than 120 years after he died, and his skeleton remains on display as the centrepiece of Hunter’s collection at the Royal College of Surgeons in London, despite the fact that it’s fairly common knowledge that Byrne explicitly did not consent for his remains to be used in this way.

Unfortunately, in Britain, while nobody can technically, legally ‘own’ a dead body, when it comes to medical/scientific specimens, which is what Byrne’s skeleton is considered to be today, possession is 9/10ths of the law, as the saying goes, and the RCS has no legal obligation to de-accession Byrne’s bones and respect his final wishes. Despite numerous calls for them to consider that they perhaps have an ethical obligation to do so, given what we know about how this particular specimen was obtained, the trustees maintain that the ‘scientific’ value of the skeleton is too great, and that the ability of visitors to the Hunterian museum to continue to gawk at Byrne the object (just like those bored Londoners of the 1780’s) matters more than recognizing Byrne the man, and righting a historical wrong. So that’s something to think about if visiting the Hunterian Museum is on your list of things to do in London.

Further reading:

Most of the information for this post was drawn from two sources in particular. This Brief Life History of Byrne by an uncredited author, and the 2013 article by Thomas Muinzer, A Grave Situation: An Examination of the Legal Issues Raised by the Life and Death of Charles Byrne, the “Irish Giant”. You can find a copy of Muinzer’s article on academia.edu (I am not sure of the politics of linking directly to that sort of thing), and I highly recommend it both for the background information on Byrne’s life (and death) as well as his discussion on the legal circumstances of the case both as they would have applied in 1783, and as they apply today. He also makes a really interesting case for where (and why) Byrne’s remains should be buried if they were to be released by the Hunterian museum.

Very interesting, a good read. I also think that Byrne’s body should be laid to rest in the way he wanted

LikeLike

Awesome blog man!

LikeLike